Super-Long Exposure Photography - A Vague Monologue

Blossoms In Madrid - 24mm, 365 sec, f/8.0, ISO 100

Long exposure photography is a style that I immediately wanted to replicate when I got hold of my first DSLR. I found it fascinating that you could force the camera to see in the dark or blur fast moving water just by forcing the shutter open longer than usual.

A quick peruse on 500px or flickr tells me that I’m probably not alone in finding long exposure photography eye-catching...If it’s not an image of a silky smooth Icelandic waterfall at sunset that you find on the front page, then it’s car light trails disappearing off into a dark, dystopian cityscape.

In 2015, I watched a video, by Brendan Van Son (click for link), about trying to find a use for the Formatt-Hitech 16 Stop ND (Neutral Density) Filter. It blocked out so much light that it allowed for incredibly long exposures in the middle of the day. I resolved that I had to own one.

Super-long exposures?

Essentially, It's taking long exposure photography to its logical extreme. Keeping the camera's shutter open until it starts to cry. The image of the blossoms here, for example, has a shutter speed of 365 seconds and was taken in broad day light in the Spanish sun. To put that in perspective, some of the most impressive shots of the Milky Way that you see, with all their fine detail and structure, are taken in absolute darkness and might rack up a shutter speed of less than 30 seconds.

Whilst astro-photographers are actively trying to soak up every photon of light that they can, daytime long exposures have to block out as much as possible whilst still capturing some kind of image. This is where a 16 stop filter comes into play.

When shooting in broad daylight, possibly with a bit of cloud, your camera might meter for a landscape photo at, say 1/200 sec at f/8. With a 10 stop filter, such as the Lee Big Stopper, you would extend this time to a shutter speed of around 5 seconds. The 16 stop requires that you leave that shutter open for 5 minutes 27 seconds.

Why do it?

Mary's Shell - Nikon D750, 85mm, 249 sec, f/5.6, ISO 100

The pay off for standing around waiting for this single exposure is silky clouds on blue skies, water that looks like it’s entirely ethereal and, if you point your camera at a crowded tourist hotspot, an almost entirely empty Trafalgar Square.

There's something novel and striking about having a single object standing inanimately whilst time passes it by. It removes the clutter, making the images look so much cleaner than if they had slower shutter speeds. The Mary's Shell photo for example was taken as the tide started coming in and covered the art installation. There were waves, water swirling around and shadows of passing clouds that were all 'averaged' out of the shot, just because the image took so long to expose. The resulting photo retains almost no evidence that the water was anything but a mill pond and where the water meets the sculpture, an ethereal mist floats above the surface. To my mind, it's impossible to otherwise that style without some very clever editing.

The Issues

However.

The trade off for this, apart from standing around praying that a dog doesn't run into your tripod, is that cameras are really not designed well for this type of treatment, but with a bit of help, they can just about manage it.

Light Leaks

Light pours into your camera in daylight, like water into a sieve thrown into a swimming pool. Normally it’s not a problem, because it’s meant to. We buy lenses for the express purpose of directing light at the sensor. But when you cover the primary means of light-ingress up with, what essentially amounts to, welding goggles, any other source suddenly becomes grossly over exaggerated.

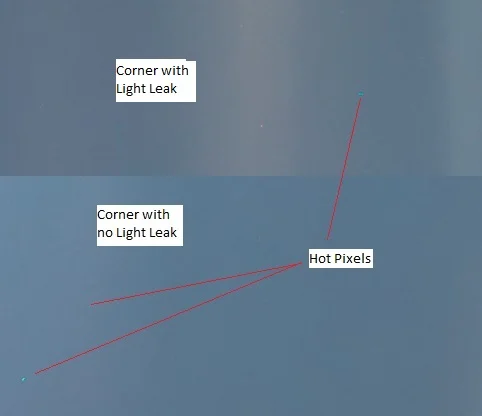

This was taken from the the upper left hand corner of the Madrid in Blossom image, the top section was my first shot which I didn't shield from the sun. The bottom image is taken from an identical shot but with the camera suitably shaded.

The view finder is the primary culprit here, as it is with other forms of long exposure photography, colour fringing creates horribly discoloured vignetting that’s very difficult to fix in post processing. I simply use a hat to cover up the camera. It saves swapping out the eye piece for the easily losable cover that Nikon cameras come with.

Hot Pixels

If you’ve tried long exposures of the night sky, you’ll know that hot pixels are an unfortunately unavoidable consequence of your camera’s sensor being active for too long. Usually they’re harmless and can pass unnoticed with a bit of noise reductions, or a quick clean up in Photoshop. But past a certain point, it just becomes impossible, the only way of removing this scale of noise becomes dark frame subtraction.

Glare

Filters are always prone to a bit of glare now and again. It’s the nature of the beast, more glass means more shiney bits for the light to reflect off. With exposures that can last up to 10 minutes, you have to pray that no new light source points down your lens whilst you wait, because there’s no way you’ll notice that your photo is ruined until it’s finished.

The Changing Scene

This is probably the most abstract problem that you have to get to grips with when photographing such long exposures during the day. The light changes. All the time. What you metered for at the start of the exposure, isn’t necessarily what the light is like by the end of your exposure. Or at any point in between, for that matter.

The problem is, how do you meter for this? Essentially, you can’t, but keeping an eye on the scene and taking an educated guess at how the light averages out over the course of the exposure seems to roughly work...usually.

The Reward

The before

Images from super-long exposures are some of those that I find the most rewarding. Maybe it's the surreal, ethereal landscapes they produce, where the subject stands still as time passes by. Maybe the inordinate number of technical hurdles that you have to pass before you can even contemplate salvaging an image from the the train-wreck of abused equipment that makes the success even sweeter... Either way there's something about them that make me keep trying.

The After